|

Brute-Force Analysis in Go by Richard Bozulich © Copyright 2015 by Richard Bozulich All rights reserved according to international law. No part of this work may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied for public or private use without written permission from Kiseido Publishing Company. Chigasaki, Japan |

|

Go is played on a very large board, consisting of 361 playing points. During the opening stage, a player must consider a number of candidate moves, then anticipate the possible responses of his opponent. For each of these responses he must consider what his own response will be, and so on. An enormous amount of data must be kept track of. Clearly, an exhaustive search is impractical, so an expert go player needs some principles to guide him or her in finding the best move. Using these principles to come up with a move is what is referred to as intuition. As the game progresses, skirmishes arise in various parts of the board. The areas in which these skirmishes arise are limited in size, so the number of candidate moves to consider is greatly reduced to ten and often much fewer. In such positions, brute-force analysis (or reading, as go players usually refer to it) becomes feasible. However, even after a successful analysis is completed, the result must be evaluated in relation to positions in other parts of the board; this is also a kind of intuition. Even when brute-force analysis is required, intuition also plays a role in one's ability to instantly find the key move. Those key moves are called tesujis. There are about 45 different kinds of tesujis that a dan-ranked go player should be familiar with. If a player has solved many problems that involve a certain kind of tesuji, he or she will immediately recognize, almost unconsciously, positions in their games where that tesuji is applicable. This is called 'pattern recognition'. Of course the player must confirm that it is indeed the required tesuji by reading out the continuation. In summary, anyone who aspires to achieve the lofty ranks of dan-level play must learn the basic principles of the opening and solve hundreds, if not thousands, of life-and-death and tesuji problems. Here is an example of how a knowledge of the basic tesujis can provide the intuition to find the best move in a game. |

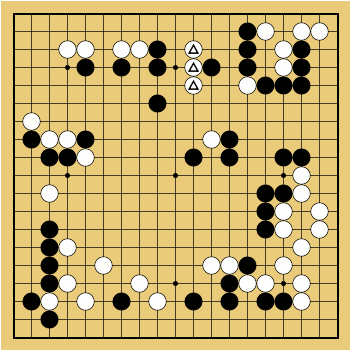

Dia. 1 |

In Dia. 1, White's marked stones are isolated within Black's sphere of influence. If White is unable to rescue these stones, Black will win.

|

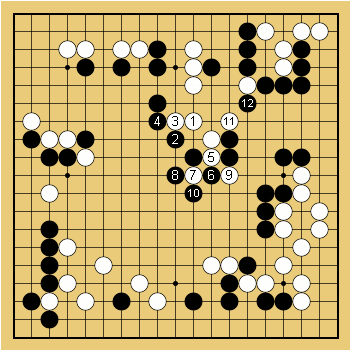

Dia. 2 |

If White tries to break out with an ordinary move such as jumping to 1 in Dia. 2, Black can prevent the white stones from escaping by playing the moves from 2 to 12. White's stones are trapped and there is no way to make two eyes for them. |

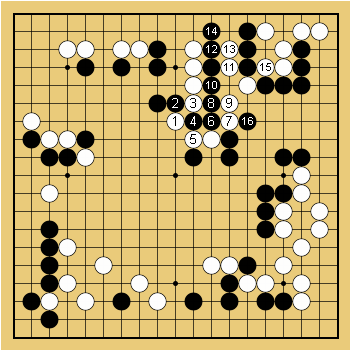

Dia. 3 |

Trying to escape with the knight's move of 1 in Dia. 3 also fails, as the moves to Black 16 show. |

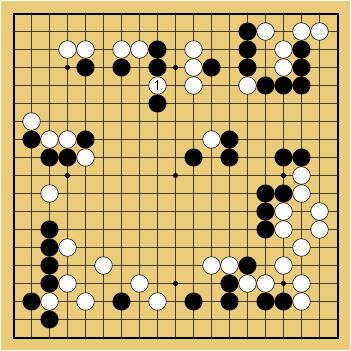

Dia. 4 |

There is only one move that enables White to escape with his stranded stones: the wedge-in of White 1 in Dia. 4. This is not an easy move to see and it is unlikely that kyu-level players would even consider it unless they had already studied tesujis rather extensively. Moves like this are blind spots for kyu players. However, a player of high-dan-level strength would spot this tesuji immediately, almost without any thought. We might say that he found it by intuition. Once having found it, though, the player must confirm that it is indeed a tesuji. This is where the brute-force analysis or reading must be done. |

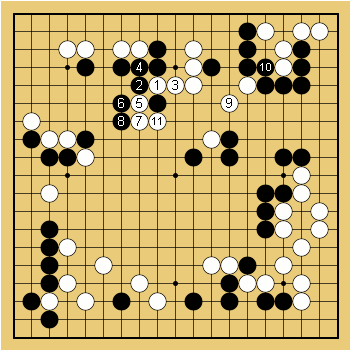

Dia. 5 |

After the wedge-in tesuji of White 1, Black might atari from the left in Dia. 5. White extends to 3 and Black has to connect at 4. White cuts with 5 and Black must atari with 6 and 8 to prevent his stones on the top left from being isolated. White 9 forces Black to defend with 10, so White's stones will have no trouble escaping after 11. |

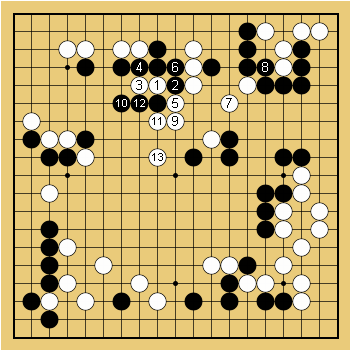

Dia. 6 |

Black could also answer White 1 with an atari from the right with 2 in Dia. 6. White would then extend to 3, forcing Black to connect at 4. White now cuts with 5 and plays a diagonal move with 7; Black must connect with 8. White now sacrifices two stones with the atari of 11, then escapes into the center with his other stones by jumping to 13, where they will eventually link up with their allies at the bottom. Diagrams 5 and 6 are only a partial analysis of the moves a player should consider. |

|

In conclusion, intuition is not something mysterious that comes into our consciousness from out of the blue or from some unknown realm that inspires us. It comes from the knowledge of general principles and techniques that can be applied in a wide variety of situations. Mathematical Tesujis The situation in mathematics is similar. Proving a theorem requires a knowledge of a wide range of techniques that might be called mathematical tesujis. As the novice mathematician gains maturity, these techniques provide deep insight into mathematical theories. A simple example of a mathematical tesuji that high-school students learn when studying geometry is proof by contradiction. A wide variety of geometry theorems as well as many arithmetical ones can be proven using this 'tesuji'. A famous example is the theorem 'The square root of two is an irrational number.' In the calculus it is often necessary to integrate complicated functions and there are numerous techniques ('tesujis') for doing this, such as, substitutions, completing the square, by parts, etc. A Survey of the Basic Tesujis is a collection of the more than 40 basic tesujis that arise in the game of go. After an example of each tesuji is presented and explained, three to 12 problems follow, showing the various ways that they can be applied. The aim of this book is to create an awareness of all the tesuji that can arise in a game. If you are a high-kyu-level player studying this book, your intuition may not yet be well developed, so it will be hard to spot the correct tesuji. However, you should not dwell too long on each problem. It is better to look on them as examples, make a good-guess move, then immediately look at the answer. In this way you can probably do about 20 problems in an hour, getting through the entire book in about a week. Your mind will be working full-time, even while you are sleeping, to internalize the new knowledge that is being crammed into your brain, but your intuition will be gradually developing. After finishing the entire book, go through it again. Your mind will have already absorbed much of the new knowledge and will recognize many patterns that keep recurring. After going through the book twice at high speed, you can then come back to it a third time and look at the moves in more detail to confirm that the tesujis actually work. By developing your intuition in this way, you will start spotting similar tesuji in your own games. After you have familiarized yourself with all the tesujis presented in the above book, you should follow up with 501 Tesuji Problems. The 45 basic tesujis in this collection are presented in random order, so it is similar to coming across them in a game. Instead of skimming through these problems as was suggested for A Survey of the Basic Tesujis, you should make a serious effort to solve each problem. But don't spend too much time on them. If you are are stumped, looking at the answer will help you identify your blind spots. Below are some other tesuji books published by Kiseido. Pondering and solving the problems in these books will help you spot the tesujis that lurk beneath the positions in your games. Get Strong at Tesuji A collection of 534 easy to moderately difficult tesuji problems. 300 Tesuji Problems, 5-kyu to 3-dan 300 Tesuji Problems, 4-dan to 7-dan |